Maritime Chokepoints are Critical to Global Energy Security

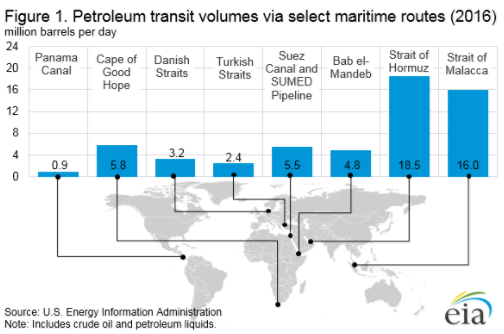

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) has released its 2017 World Oil Transit Chokepoints report highlighting chokepoints that are part of major trade routes for global seaborne oil transportation (Figure 1). Chokepoints are narrow channels along widely used global sea routes for oil transport, with some so narrow that restrictions are placed on the size of the vessel that can navigate through them. Chokepoints are critical to global energy security.

The inability of oil to transit a major chokepoint, even temporarily, can lead to substantial supply delays and higher shipping costs, resulting in higher world energy prices. While most chokepoints can be circumvented through the use of other routes that add significantly to transit time, there are no practical alternatives in some cases. Chokepoints may also expose oil tankers to theft from pirates, terrorist attacks, political unrest (in the form of wars or hostilities), and shipping accidents that can lead to oil spills.

Three of the more important maritime chokepoints are located around the Arabian Peninsula: the Strait of Hormuz, the Bab el-Mandeb, and the Suez Canal and Suez-Mediterranean (SUMED) Pipeline (Figure 2).

A description of the four largest chokepoints by global petroleum transit volumes follows.

Strait of Hormuz

Located between Oman and Iran, the Strait of Hormuz connects the Persian Gulf with the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian Sea. The Strait of Hormuz is the world’s most important oil chokepoint. About 17 million barrels per day (b/d) flowed through it in 2015, which accounted for nearly 30% of all seaborne-traded crude oil and other liquids. The volume that traveled through this vital choke point increased to 18.5 million b/d in 2016.

EIA estimates that about 80% of the crude oil that moved through this chokepoint in 2016 went to Asian markets, based on data from Lloyd’s List Intelligence tanker tracking service. China, Japan, India, South Korea, and Singapore are the largest destinations for oil moving through the Strait of Hormuz.

Strait of Malacca

The Strait of Malacca, which flows between Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, connects the Indian Ocean with the Pacific Ocean via the South China Sea. It is the shortest sea route between the Middle East and growing Asian markets (Figure 3). Flows through the Strait of Malacca were 16 million b/d in 2016, making it the second busiest global transit chokepoint and the busiest outside the Arabian Peninsula.

Oil shipments through the Strait of Malacca supply China and Indonesia, two of the world’s fastest growing economies. The Strait of Malacca is the primary chokepoint in Asia; in recent years, between 85% and 90% of annual total petroleum flows through this chokepoint were crude oil.

If the Strait of Malacca were blocked, nearly half of the world’s fleet would be required to reroute around the Indonesian archipelago, such as through the Lombok Strait between the Indonesian islands of Bali and Lombok or through the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra. Rerouting would tie up global shipping capacity, add to shipping costs, and potentially affect energy prices.

Suez Canal and the SUMED Pipeline

The Suez Canal and the SUMED Pipeline are strategic routes for Persian Gulf oil and natural gas shipments to Europe and North America. These two routes combined accounted for about 9% of the world’s seaborne oil trade in 2015.

Located in Egypt, the Suez Canal connects the Red Sea and the Gulf of Suez with the Mediterranean Sea. In 2016, 3.9 million b/d of total oil (crude oil and refined products) transited the Suez Canal in both directions, according to data published by the Suez Canal Authority. Northbound flows rose by about 300,000 b/d in 2016, but southbound shipments decreased for the first time since at least 2009. Increased crude oil exports from Iraq and Saudi Arabia to Europe contributed to higher northbound traffic, while lower exports of petroleum products from Russia to Asia contributed the most to decreased southbound traffic.

Most oil transiting the Suez Canal (2.4 million b/d) was sent northbound toward European and North American markets, while the remainder (1.5 million b/d) was sent southbound, mainly toward Asian markets. Oil exports from Persian Gulf countries (Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Iran, Oman, Qatar, and Bahrain) accounted for 84% of Suez Canal northbound oil flows. The largest importers of northbound oil flows through the Suez Canal in 2016 were European countries (78%) and the United States (14%). Oil exports from Russia accounted for the largest share (17%) of Suez southbound oil flows, followed by Turkey (15%) and the Netherlands (11%). North Africa (Algeria and Libya) made up 12% of the southbound flow. The largest importers of Suez southbound oil flows were Asian countries, with Singapore, China, and India accounting for more than 50% of the total.The 200-mile long SUMED Pipeline transports crude oil through Egypt from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. The crude oil flows through two parallel 42-inch pipelines that have a total capacity of 2.34 million b/d. The SUMED Pipeline is the only alternate route to transport crude oil from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea if ships cannot navigate through the Suez Canal. Closure of the Suez Canal and the SUMED Pipeline would require oil tankers to divert around the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa, which would add approximately 2,700 miles to the transit from Saudi Arabia to the United States. The increased transit time would also increase costs, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation. In 2016, 1.6 million b/d of crude oil was transported through the SUMED Pipeline to the Mediterranean Sea and then loaded onto tankers for seaborne trade.

Bab el-Mandeb Strait

The Bab el-Mandeb Strait is a chokepoint between the Horn of Africa and the Middle East and is a strategic link between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean. Located between Yemen, Djibouti, and Eritrea, it connects the Red Sea with the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea. Most exports from the Persian Gulf that transit the Suez Canal and the SUMED Pipeline also pass through Bab el-Mandeb. An estimated 4.8 million b/d of crude oil and refined petroleum products flowed through this waterway in 2016 toward Europe, the United States, and Asia, an increase from 3.3 million b/d in 2011.

Other global chokepoints

EIA’s recent report also highlights the chokepoints of the Turkish Straits, the Danish Straits, and the Panama Canal, as well as the important maritime route around the Cape of Good Hope.

This article is part of Daily Market News & Insights

Tagged:

MARKET CONDITION REPORT - DISCLAIMER

The information contained herein is derived from sources believed to be reliable; however, this information is not guaranteed as to its accuracy or completeness. Furthermore, no responsibility is assumed for use of this material and no express or implied warranties or guarantees are made. This material and any view or comment expressed herein are provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed in any way as an inducement or recommendation to buy or sell products, commodity futures or options contracts.